Therapy cases can get labeled as “stuck” or “impossible” with clients mistakenly seen as unmotivated or resistant. The implications of mislabeling can range from failure to engage parents in treatment, increased no show rates, premature terminations, unnecessary placement of children into foster care, and no relief for mental health symptoms.

This month’s playbook will highlight the top reasons why mislabeling occurs along with a case study to illustrate family therapy techniques using my “Get the Lights On” playbook.

Case Description

The trauma playbook uses family therapy techniques with 15-year-old Jamel and his family.

- Jamel is a crossover youth involved in both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems.

- Jamel’s mom, Tonya, has been unable to pay the utility bills and is close to receiving an eviction notice. The house has no lights or heat.

- Child Protective Services (CPS) is involved with eminent risk of removal of Jamel and his other five brothers and sisters.

- Jamel is a member of a street gang and was charged with grand theft auto. As a result, Jamal has a juvenile probation officer and must attend community service classes.

- Jamel sleeps in class, his grades are failing, and he has many unexcused absences from school.

- His mom is unemployed and clinically depressed. She feels isolated with little emotional or financial support.

- Mom’s live-in boyfriend, Rick, is presently distant and not connected to Jamel.

- Jamel’s father has little to no contact with him.

The therapist assigned to Jamel’s family asked for a consultation to learn family therapy techniques. The case had been “stuck” for over a year. The therapist primarily treated mom and Jamel using individual counseling.

Why Is This Case Stuck or Impossible?

#1- Hierarchy of Need Violations

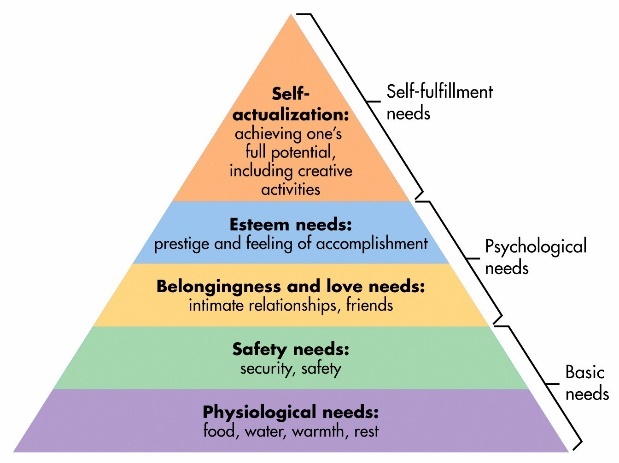

The first reason why this case was stuck is due to the therapist’s primary focus on the psychological needs of the family (i.e., intimacy, parenting skills, depression, parent-child relationships, etc.) without first addressing the family’s basic needs (i.e., food, clothing, and shelter). This relationship between basic vs. psychological needs is best illustrated through Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs or the five-tier model of human needs shown in Figure 1. Maslow stated that individuals must achieve basic needs (physiological and safety) before moving to the higher needs such of psychological or self-fulfillment.

When the hierarchy of needs is violated, clients or families can appear stuck or unmotivated due to the underlying need for food, clothing, or shelter. In Jamel’s case, there was a high risk for removal by Child Protective Services (CPS) because of neglect issues stemming from housing, not physical or mental abuse. The therapist, however, focused on family therapy techniques such as getting the mom to attend parenting classes or implementing behavioral modification contracts.

The mother was labeled as clinically depressed. But a better reframe is that mom’s depression was a typical reaction to being overstressed and overwhelmed. We might also be depressed if we had no job, housing insecurity, the risk that our children might be removed for neglect and little outside support.

Tonya, the mother, needed a concrete plan for paying for the utilities and mobilizing a support system before she could muster the energy or bandwidth to address psychological or fulfillment needs with herself and her son.

My first step was to help the therapist see the case from the hierarchy of needs lens and to help her design a trauma playbook addressing both basic and safety requirements with appropriate family therapy techniques. Clarity of roles and mobilizing the extended family or village was also needed.

#2- A Lack of Systemic Thinking

Closely related to the hierarchy of need violations was a lack of systemic thinking. A therapist must be trained in systems/family therapy to mobilize a stuck family system around basic needs. Without systemic thinking, the therapist will likely try to solve a basic need issue with only client-centered therapy, as in Jamel’s case.

What was needed was a “town meeting.” Using this approach, the mother, the father, the boyfriend, the caseworker, the probation officer, and any extended family or friends are brought together in one room with clear directions to create a written plan of action to “get the lights on” and to support the mother and entire family. In Jamel’s case, this type of intervention had not happened because the therapist’s graduate work was psychodynamic and focused on the individual. As a result, the family received only individual treatment.

Dr. Sells, you want me to be perfectly honest? We don’t do family therapy because it scares us to death. We lack the step-by-step tools, training, and confidence.

This sentiment is widespread across mental health. This fear was one of the main reasons why we wrote a family trauma book with step-by-step tools and trauma playbooks to increase your confidence and comfort level dramatically. Once Jamel’s therapist was successful in family therapy using this playbook she has never looked back.

#3- Disconnect Between the CPS Case Plan and Non-Systemic Treatment

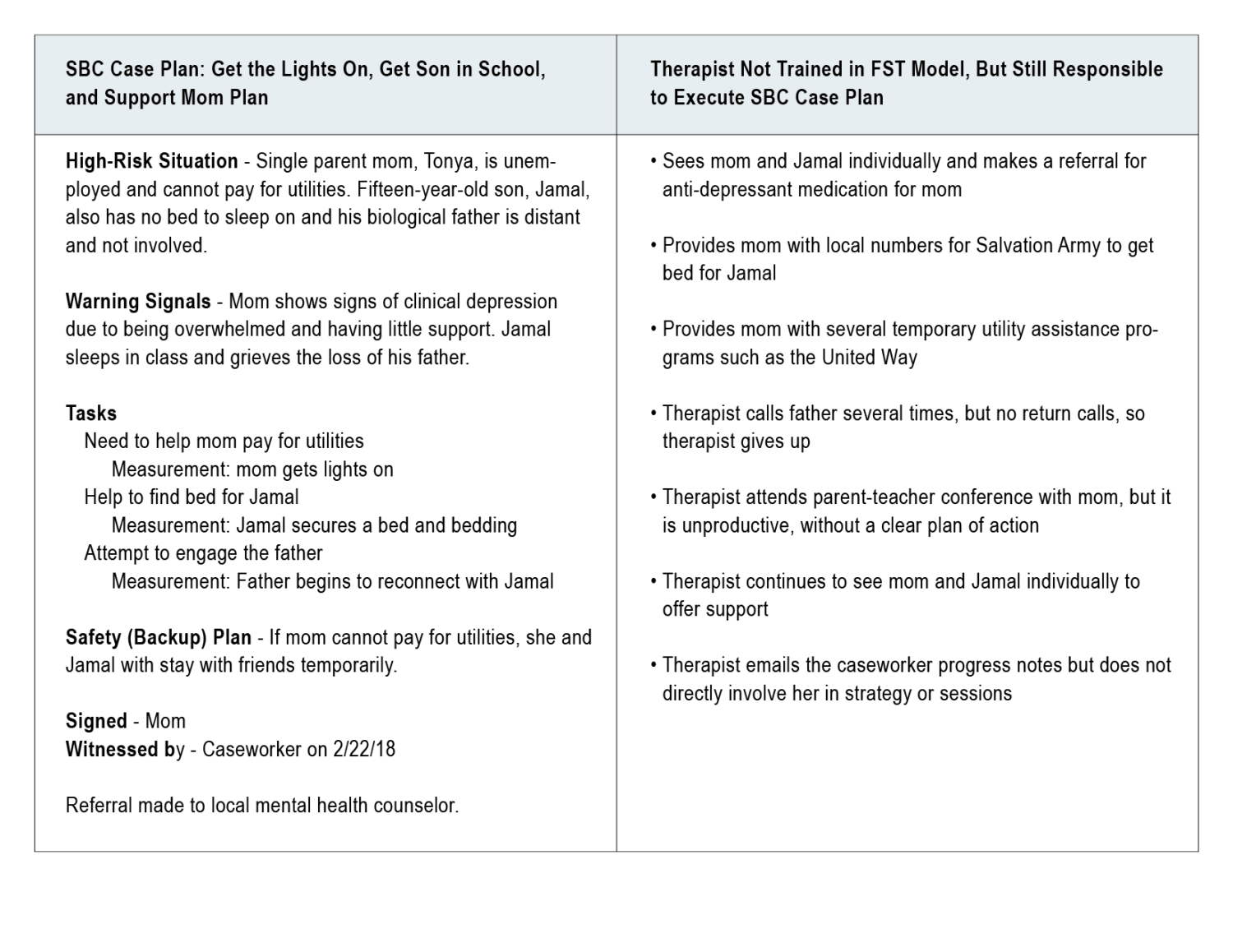

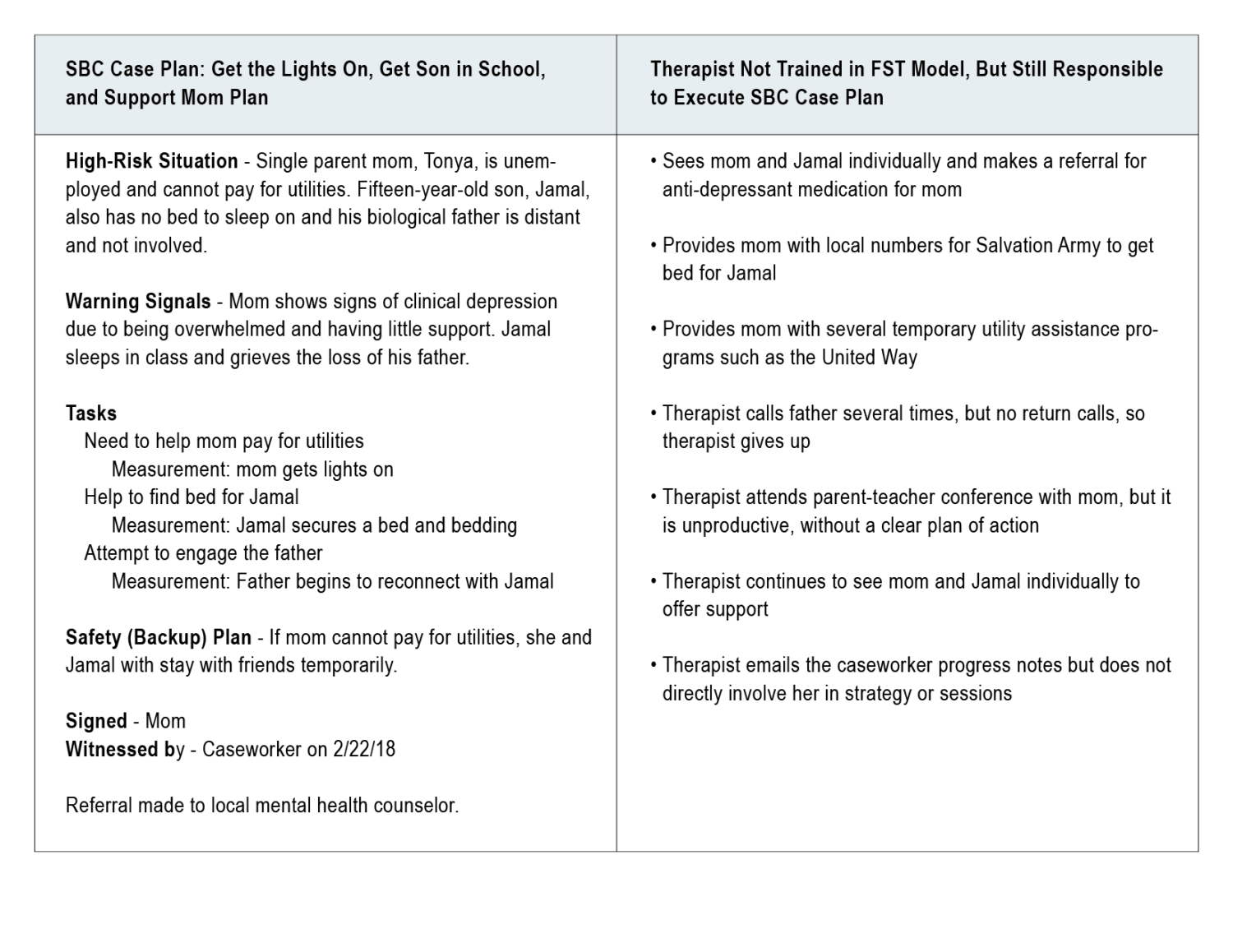

In Table 1, one can see the disconnect between the CPS caseworkers Solution-Based Casework (SBC) Action Plan and its execution by the therapist with a non-systemic lens. Solution-Based Casework (SBC) is an evidence-based case management model teaching caseworkers how to be strength-based and develop both a measurable individual and family plan.

Table 1 illustrates the SBC action case plan created by the caseworker and family. The plan had clear tasks to address Maslow’s Basic Needs and the goal of getting mom support and helping Jamal get to school. The caseworker then referred the family to the local mental health therapist to execute and implement the family therapy techniques. However, the therapist for this case lacked the systems tools in the Family Systems Trauma – FST Model or how to create a trauma playbook. As a result, the theory of the case plan did not translate into successful implementation and the family remained stuck.

Table 1: Jamel’s CPS Case Plan vs. The Initial Therapeutic Plan

Several concrete examples below illustrate the disconnect between case plan theory and successful therapeutic execution:

- It is clear from the SBC case plan that mom is depressed, overwhelmed, and lacks support.The therapist from a non-systemic lens sees mom and son individually instead of mobilizing boyfriend, caseworker, probation officer, and local pastor in a “town meeting” to help mom and son.

- The SBC case plan clearly states that mom needs assistance to get utilities on and a bed for Jamal.The therapist executed this initiative by providing community referral information. The mom, however, lacked the energy, expertise, or bandwidth to do this on her own. The therapist was well-intentioned but did not have the systems training or tools to organize a family therapy session to show the mother and her village to do it themselves as outlined in the Trauma Playbook in Figure 2 below.

- The SBC case plan also outlined the importance of engaging the father and boyfriend. The therapist was not trained in family systems engagement or the use of the motivational phone call techniques of the FST model. Therefore, after a few attempts and no response, the therapist gave up.

In summary, there was a lack of synchronicity between the case plan and its actual application in therapy. The therapeutic system and the CPS case management system worked in silos, and the therapist lacked the tools or training to go from treating the traumatized child to the traumatized family.

Please Note: Clients “will do well if they can” but only if they have the right tools and a therapist/coach to show them how to use them with typed out playbooks and dress rehearsals.

Case Example

Jamal’s case is briefly highlighted in Chapter 7 of Treating the Traumatized Child: A Step-by-Step Family Systems Approach. Once I met with the family and regrouped with the therapist, we changed treatment paradigm from a client-centered to a family systems trauma (FST) approach. The significant shifts in the case are highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2: Shifting From A Client-Centered to

A Family Systems Trauma Approach

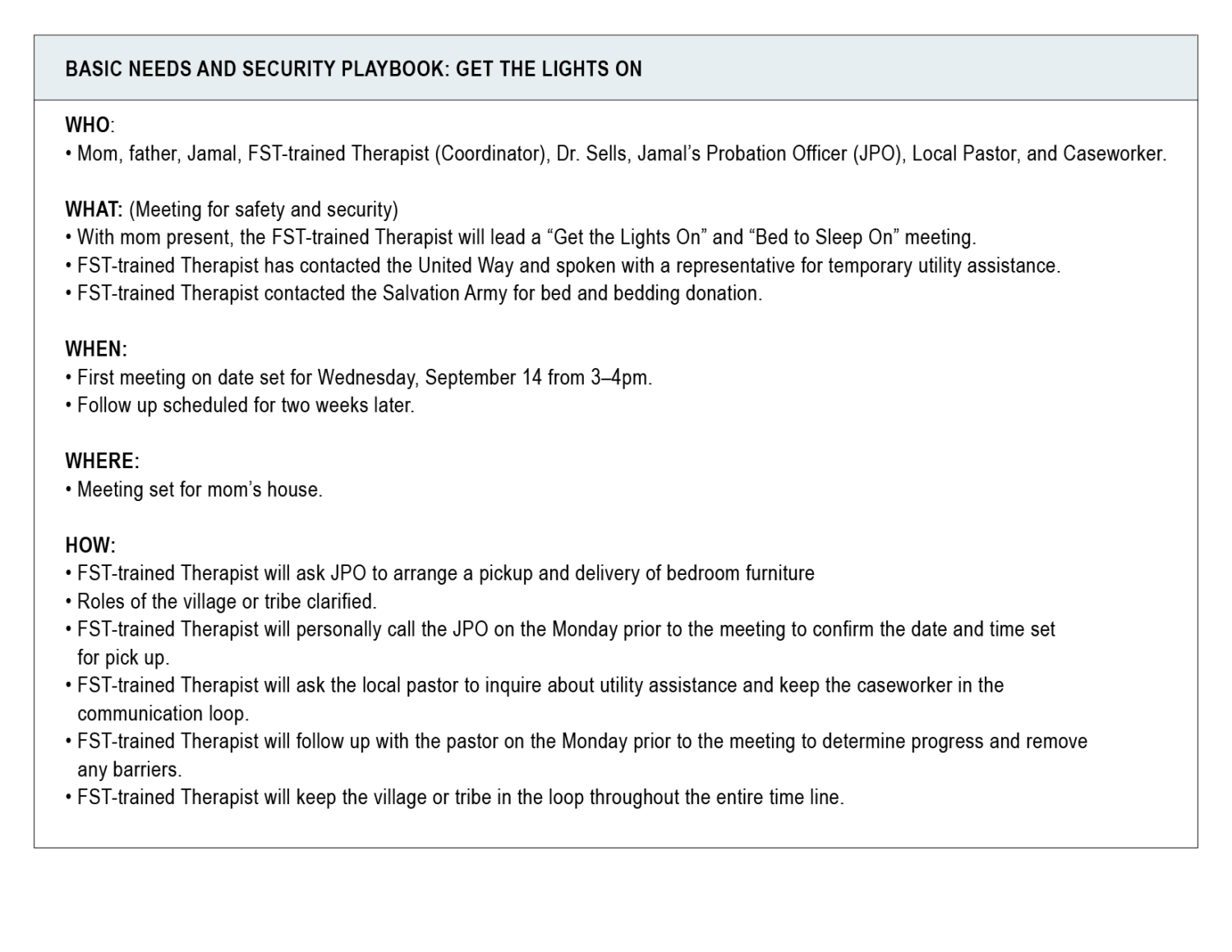

As Table 3 highlights, the trauma playbook is a visual illustration of both the therapist’s family systems trauma model paradigm shift and what a good trauma playbook can do to reenergize and move a chronically stuck case:

Table 3: Basic Needs and Security Playbook: Get the Lights On

What Did We Learn?

After the Trauma Playbook is presented, everyone feels a sense of hope and is energized. Roles are clarified in writing, and the father is not blamed for the past but what can take place in the here and now.

As a reminder: You can send a stuck case for consideration to be reviewed and highlighted with family therapy techniques in the playbook section. Please email us at info@familytrauma.com. If your case is selected, Dr. Sells will contact you directly.

Scott P. Sells, PhD, MSW, LCSW, LMFT, is the author of three books, Treating the Tough Adolescent: A Family-Based, Step-by-Step Guide (1998), Parenting Your Out-of-Control Teenager: 7 Steps to Reestablish Authority and Reclaim Love (2001), and Treating the Traumatized Child: A Step-by Step Family Systems Approach (2017). He can be contacted at spsells@familytrauma.com or through LinkedIn.