The FST Trauma Safety Playbook

I will never forget the phone call. Sarah, a highly competent trauma therapist, contacted me and said:

Scott, I am stuck with this family. I have been seeing them for over ten months with little to no significant change. Fifteen-year-old Leon is now involved in both the juvenile justice system for stealing a car and also the child welfare system. Leon’s single-parent mom, Juanita, has not paid utilities in months, there is no bed for him to sleep on and little food in the house. As a result, he and his three younger brothers are at risk for placement into foster care. Even worse, Juanita is clinically depressed, Leon refuses to attend school, and does not show up for his probation community services classes. I have also been unable to engage Leon’s dad or Juanita’s current boyfriend. I left one voicemail for the dad with no return call and the boyfriend is not responsive. For the last ten months, I have been seeing Juanita individually for her depression and providing parenting tools for Leon and his siblings. But I can’t figure out why it’s not working, and the family is falling deeper into crisis. Can you help?

What Went Wrong?

This situation is a vital case description regarding the importance of safety first. Within the FST | Family Systems Trauma Model, the trauma therapist must decide between:

- Stabilize safety first (i.e., parent-child conflict, neglect issues, extreme acting out child behaviors, self-harm, drug abuse, bullying, etc.),

or

- Active trauma treatment first (i.e., unresolved grief, abandonment, family secrets, anxiety, lack of nurturance, etc.).

We discuss this important decision in greater detail using what is called the “three rules of thumb” in the article entitled: FST Stabilization vs. Active Trauma Technique: Setting the Goals of Therapy.

I compare this safety stabilization vs. active trauma first choice to the decisions emergency room doctors must make when a patient with a bleeding gunshot wound enters the ER. The doctor must quickly assess what to do first: stop the bleeding or remove the bullet? The bleeding represents the immediate safety concerns, and the bullet represents the cause of the trauma. A wrong decision can curtail the healing process or even cost the patient his or her life.

My colleague Sarah was stuck with Leon’s case because safety first was not addressed in two specific areas:

#1. Hierarchy of Need Safety Violations

The first reason was Sarah’s tactical decision to focus on this family’s trauma or psychological needs (i.e., parenting skills, depression, parent-child relationships, etc.) without first addressing the family’s basic safety needs of food, clothing, and shelter.

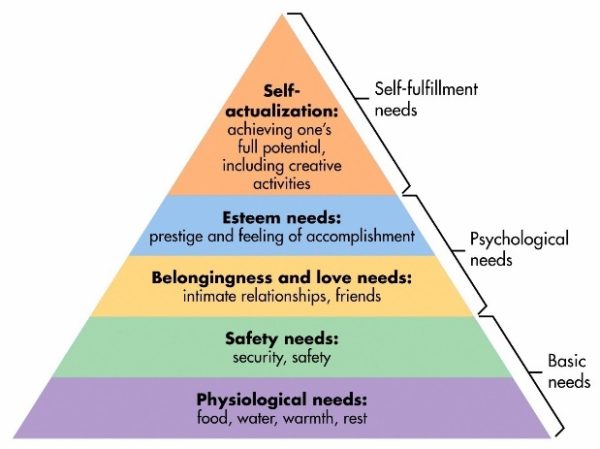

This relationship between basic vs. psychological needs is illustrated through Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs or the five-tier model of human needs shown in Figure 1. Maslow states that individuals must achieve basic needs first (physiological and safety) before moving to higher needs, such as psychological or self-fulfillment.

In turn, when safety needs are neglected, problem symptoms and negative repercussions take place. In Leon’s case, not having a bed to sleep on or adequate food led to a chain reaction of sleeping in class, an inability to focus, negative attitudes by his teachers, and getting further behind academically. Leon then had no interest in attending school or reason to go to his probation community services classes.

In addition, there is now a high risk for removal by Child Protective Services (CPS) due to neglect issues from a lack of basic needs, not physical or mental abuse.

Sarah, however, focused on active trauma treatment surrounding the mom’s clinical depression and parent-child conflict using behavioral modification contracts.

The mother was labeled as clinically depressed. But a better reframe is that her depression was a normal reaction to being overstressed and overwhelmed. We would also be depressed if we had no job, experienced housing insecurity, and dealt with the risk that our children might be removed for neglect.

In short, Leon’s family needed stabilization first through safety planning but instead received a steady dosage of trauma treatment to address Maslow’s psychological needs of esteem, love, and belonging.

Timing is everything. And the timing was a misfire for Leon’s family.

#2. A Lack of a Written Trauma Playbook

Leon’s family needed a written safety first plan of action that involved paying for the utilities and mobilizing a support system before the mother, Juanita, could muster the energy or bandwidth to address psychological trauma with herself and her children.

What was needed was a “town meeting” approach where the mother, the father, the boyfriend, the caseworker, the probation officer, and any extended family or friends are brought together in one room with clear directions to create a written plan of action to “get the lights on” and to support the mother and entire family.

At the Family Trauma Institute and within the FST treatment model, we developed what are called FST Safety Trauma Playbooks. This type of safety trauma playbook was used to help unstick Leon’s family. Please see Chapter 8 of Treating the Traumatized Child: A Step-by-Step Family Systems Approach for procedures of how to create these types of playbooks for your cases.

In sum, Leon’s family and Sarah remained stuck within this second area based on the following reasons:

- Sarah saw Juanita and Leon individually instead of mobilizing the boyfriend, caseworker, probation officer, and local pastor in a “town meeting” to help mom and son. The extended family was never contacted in the entire ten months of treatment. Sarah lacked family systems trauma training. As a result, she treated the case using a non-systemic lens.

- Juanita desperately needed assistance to get the utilities on, food, and a bed for Leon. Sarah provided the mom with community referral information. However, the mom lacked the energy, expertise, or bandwidth to do this on her own. The therapist was well-intentioned but did not have the tools to organize a family therapy session to create a safety trauma playbook.

The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, even though it doesn’t work. In Leon’s case, the definition of insanity was keeping this family traumatized and stuck.

How the Case Was Unstuck Using FST Safety Planning

As a consultant, the first thing I did was to assess with Sarah and the family their current safety levels.

Step 1: Assess Current Safety Levels

To accomplish this goal, the FST therapist uses a verbal safety risk scale of 1 to 5 (1= no risk; 5 = high risk). If the parents or child state that the risk level is currently high at “3” or above, the FST therapist is faced with an important decision:

- Postpone moving forward into active trauma treatment until the risk level has dropped to lower than a 3.

This simple risk level scaling is an ideal first step to bring quick and efficient insight for both the family or the therapist to slow down with a safety first rating or to process forward with active trauma treatment if the risk level is a “3” or below.

In Leon’s family, everyone stated that they were at a “5” with mom shutting down due to her depression and the possibility of the kids being placed in temporary foster care.

Step 2: Get the Right People on the Bus

In the article entitled, How to Engage the Extended Family in Trauma Treatment, I describe the importance of “who” before “what”.

We should shift our decision [in safety planning] from a “what” question (“What should we do?”) to a “who” question (“Who would be the right person to take responsibility for this?”). Translated into treatment, this means that the therapist should spend more time on the “who” decision before launching into the “what” of treatment. It is crucial to get the right people on the bus in the right seats and the wrong people off the bus. First, we focus on the people, then the direction.

Translation: Sarah did not have the right people on this family’s bus or “the who” before “the what”. Having the right people on the bus in treatment is absolutely a critical first step in safety planning. Juanita was trying to pull the family metaphorically out of the mud with one therapist visiting one time per week and with children who had out of control behaviors. She was all alone and had no clear written plan of action.

High safety risk = crisis. When a child or family is in crisis, it is not a time for problem exploration but a time for action.

I used the techniques of the FST Motivational Phone Call and the FST Diagnostic Village Handout to quickly engage and bring together all of the key extended family members.

Step 3: Construct an FST Family Systems Playbook

When everyone was assembled, we used this FST Safety Trauma Playbook to clarify everyone’s roles within a “who, what, when, where, and how?” format.

Please note the following:

- This format allows for clarity of everyone’s role and how to realign and pull together as one team to address the safety crisis at hand. In this case, it was the need for utilities and bedding for Leon.

- In turn, the risk for CPS removal was eliminated, and the mother’s depression was remarkably better because she finally had the support that is both clear and measurable with accountability.

- Leon, in turn, started performing well in school and attending his juvenile probation community service obligations. Without the extended family and the playbook, it is unlikely that his family would decrease the safety risk below a Level 3 and get unstuck.

Conclusion

After the playbook was implemented, the family was again asked the verbal safety risk scale of 1 to 5. The mother and children now said that it was at a “2”. Mom still needed parenting tools, but her depression was lifting, and her energy and motivation had returned. In turn, with the dad now involved, Leon was like a different child. The table was now set to do active trauma and psychological treatment once stabilization was achieved with safety levels below a “3”. The case got unstuck after we knew where to tap and how to tap using a Family Systems Trauma framework.

About the Author

Scott P. Sells, Ph.D., MSW, LCSW, LMFT, is the author of three books, Treating the Tough Adolescent: A Family-Based, Step-by-Step Guide (1998), Parenting Your Out-of-Control Teenager: 7 Steps to Reestablish Authority and Reclaim Love (2001), and Treating the Traumatized Child: A Step-by-Step Family Systems Approach (2017). He can be contacted at spsells@familytrauma.com or through LinkedIn and Facebook.